First-semester, first-year Honours Pathway Option program for Biology and Environmental Science students were recently taught how to use concept maps for problem-based learning (PBL). Our aim was to develop critical thinking, teamwork and communication skills whilst promoting self-directed learning from the beginning (Davis & Harden, 1999; Srinivasan et al., 2007). Here’s how we did it:

Using expert groups, we applied a version of the jigsaw method where one expert group learnt the appropriate steps to constructing a concept map, the purpose of the maps and how they fit into the course; preparing to share their learnings with their teams in workshop 3 (Torre et al., 2013).

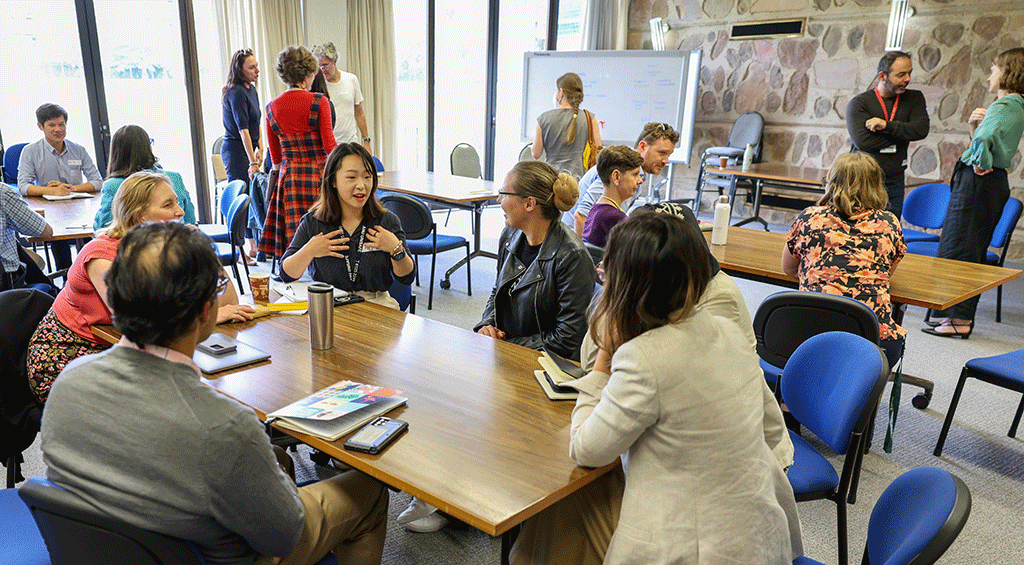

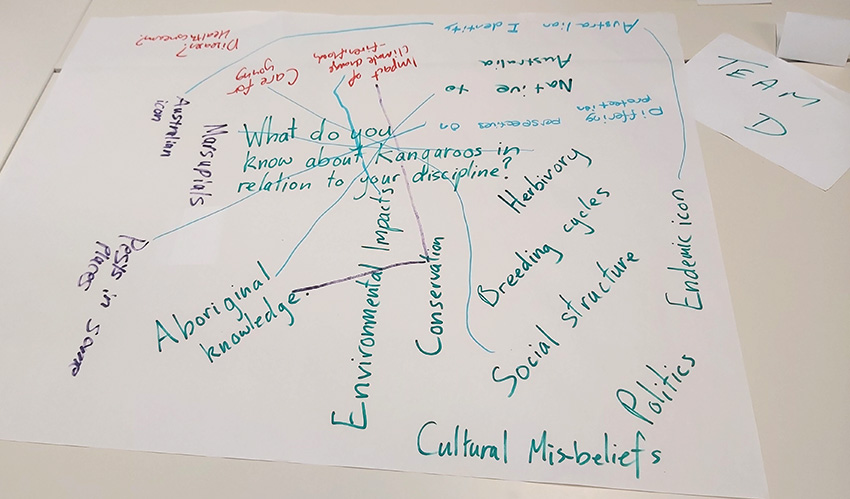

At the start of workshop 3, the expert group spent a few minutes exchanging top tips for how to construct concept maps with the entire cohort. Then within their teams, students were presented with a contemporary issue (in this case kangaroo management) and given time to struggle, define, and resolve ‘the problem’ in preparation for data collection in April and presentation in May.

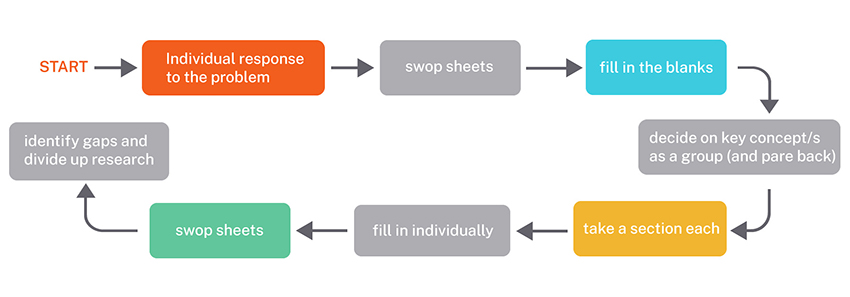

The process students followed is shown below:

In the workshop, students were given different coloured pens to add their input onto butchers paper. It was easy for both us and the students to see contributions, and how students developed their reasoning as the session progressed. Most importantly for us, the process used a combination of individual and group work so that students were able to integrate prior learning (Peñuela-Epalza& & Hoz, 2019; Veronses et al., 2013), develop their own ideas to share and then develop further as a team. Tip: If trust needs to still be built between team members, use pens of the same colour for everyone so that students feel safe in contributing.

Academics were there during the workshop to guide students back to the main learning objective if they happened to go along tangents, identified areas of weakness and common misconceptions, or were unable to find answers to their own questions (Addae et al., 2012; Veronese et al., 2013).

What was also wonderful to see was the vicarious learning that was occurring whilst the maps were being built Mayes, 2015). We were able to witness students talking through concepts step-by-step, clarifying misunderstandings, learning as individuals whilst understanding the concepts as a group (Fischer et al., 2019) along with increased student understanding of the relationships between concepts (Peñuela-Epalza & Hoz, 2019; Torre ;et al., 2013 and 2017).

Why this approach?

In our desktop research during the course design stage, we discovered that postgraduate students’ perceptions of PBL indicated that it provided focus, is particularly suited to transitioning students as they are unaware of the skills they may lack and can have problem-identifying methods to improve their skills (Srinivasan et al., 2007). According to Peñuela-Epalza & Hoz (2019), early learners can lack the skills to complete a task effectively and often have difficulty identifying how this can be remedied. Providing scaffolding can help the weaker students attain the skills to become more effective and independent in their learning further down the line. This all appeared perfect for first-year students.

For further inspiration on applying the jigsaw method here at ANU:

The jigsaw of teaching – Chris Browne’s application in engineering

Dr Scott Rickard is an Educational Designer at the Centre for Learning and Teaching

Further reading:

Addae, J. I., Wilson, J. I. & Carrington, C. (2012). Students’ perception of a modified form of PBL using concept mapping, Medical Teacher, 34:11, e756-e762, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.689440

Davis, M. H., & R.M. Harden (1999). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 15: Problem-based learning: a practical guide, Medical Teacher, 21:2, 130-140, DOI: 10.1080/014215999797

Fischer, K., Sullivan, A. M., Krupat, E. & Schwartzstein, R. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of using mechanistic concept maps in case-based collaborative learning, Academic Medicine, 94:2, 208-212, DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002445

Mayes, J.T. (2015). Still to learn from vicarious learning. E-learning and Digital Media, 12:3-4, 361-371, DOI: 10.1177/2042753015571839

Peñuela-Epalza, M. & Hoz, K. (2019). Incorporation and evaluation of serial concept maps for vertical integration and clinical reasoning in case-based learning tutorials: Perspectives of students beginning clinical medicine, Medical Teacher, 41:4, 433-440, DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1487046

Srinivasan, M., Wilkes, M., Stevenson, F., Nguyen, T. & Slavin, S. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions, Academic Medicine, 82:1, 74-82, DOI: 10.1097.ACM.000249963.93776.aa

Torre, D. M., Daley, B. J., Picho, K. & Durning, S. J. (2017). Group concept mapping: An approach to explore group knowledge organization and collaborative learning in senior medical students, Medical Teacher, 39:10, 1051-1056, DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1342030

Torre, D. M., Durning, S. J. & Daley, B. J. (2013). Twelve tips for teaching with concept maps in medical education, Medical Teacher, 35:3, 201-208, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.759644

Veronese, C. Richards, J. B., Pernar, L. Sullivan, A. M., & Schwartzstein, R.M. (2013). A randomized pilot study of the use of concept maps to enhance problem-based learning among first-year medical students, Medical Teacher, 35:9, e1478-e1484, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.785628