Transformative authentic assessment in English literary studies

In Semester 2, 2023, students enrolled in Great Writers: Gender, Authorship and History (ENGL2222) took part in a public event as part of their course assessment: the Great Writers Festival. The Festival provided a creative, innovative authentic assessment task designed to inspire students, increase engagement and develop both crucial skills in literary studies and transferrable skills for the workplace. The Festival was made possible thanks to the CLT Strategic Learning and Teaching Grants, which provided funding to ensure a professional event experience for students. This included catering and the employment of sessional staff to assist with marking and event management.

The course is designed to support students’ exploration of ‘great writers’ in literary studies. Typically, the course has focused on one writer’s oeuvre, but this semester, I decided to redesign the course to encourage an interrogation of the literary canon and the formation of ‘great writers’ across time and place. Students engaged with translations of Homer’s The Odyssey, modern adaptations like Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, modernist classics like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and compared canonical authors with pop culture stars by contrasting Shakespeare’s Sonnets with Taylor Swift’s Midnights. The final module examined Australian literature, including children’s picture books, verse novels, and Alexis Wright’s magnificent Carpentaria – encouraging students to consider Australian great writers, the role of place, and the impact of genres on our assessment of the literary canon.

Designing authentic assessment

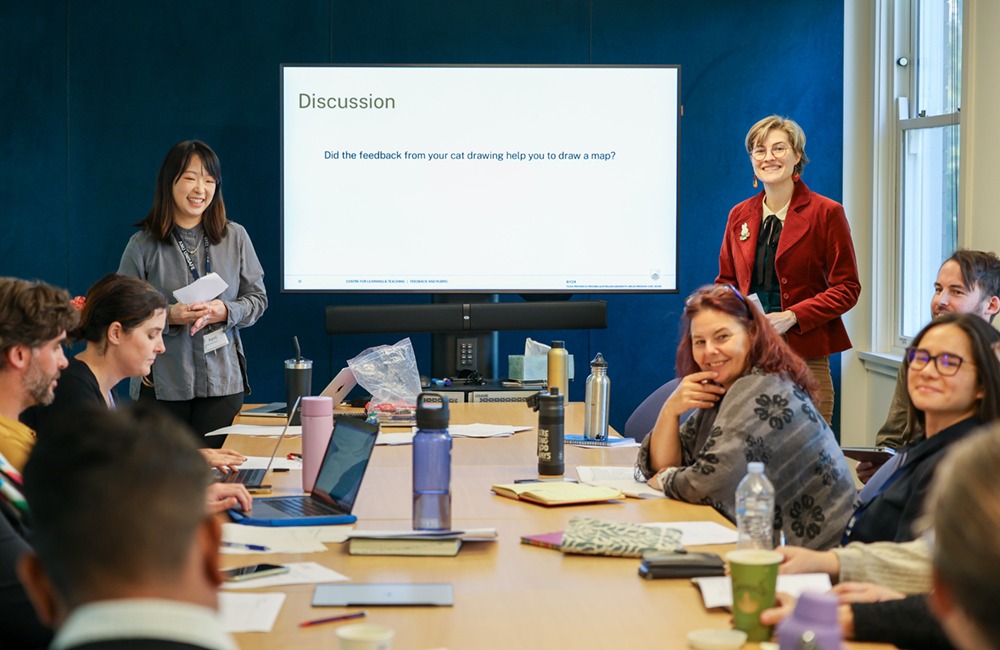

Developed in consultation with experts from the Centre for Learning and Teaching (CLT), the Festival assessment task was designed in accordance with the principles of authentic assessment.

While authentic assessment has grown apace in disciplines including STEM, health and social sciences (McArthur 86), it is far less commonly incorporated in disciplines like literary studies. Authentic assessment is contextualised, meaningful for students and linked to real-world challenges (Wiewiora & Kowalkiewicz 415; Biggs and Tang 193). It can enhance quality and depth of learning, motivation and autonomy, metacognition and self-reflection, and employability, and should have ‘relevance beyond the classroom’ (Villarroel et al. 841, 843).

One of the important aspects of genuinely authentic assessment is that it not only aligns with the ‘real world’ but is ‘directed at broader social and political change’ (McArthur 87). My Festival assessment design followed McArthur’s model, and aimed to focus not only on the ‘world of work’ but to foster a richer understanding of society, recognition of the value of the task, and emphasis on the potential for assessment to act as ‘a vehicle for transformative social change’ (McArthur 87).

Students in ENGL2222 were asked to contribute to and intervene in broader social and cultural conversations through the Festival. Through feminist interventions, analyses of Indigenous work, and consideration of the formative role of place, teams actively participated in larger sociocultural conversations about the literary canon, reinforcing that ‘authentic assessment is not assessment that mirrors the world as it is, but that which pushes the possibilities of what the world could be’ (McArthur 96).

The Festival comprised 50% of the course grade, scaffolded across the semester through a multi-stage assessment design that included both individual and group tasks. Teams could choose from a range of research questions and project types that included scholarly and creative options. Teams worked together from Week 3, producing a pitch proposal and individual research plan in Week 6, followed by the final Festival presentation and individual contribution in Week 11.

On the day

The Festival took place on 20 October, 2023 and was a public event complete with catering, a display of artwork, a programme and professional AV (audiovisual) – thanks to CLT’s strategic funding and the Kambri team. Students assisted in the setup and pack down of the event. The presentations were incredibly diverse, ranging from performances (a ‘Literature’s Next Top Model’ show, for example) to video recordings, podcast and panel discussions.

The Festival atmosphere was overwhelmingly positive and I believe gave students a sense of achievement and acknowledgment in a way that conventional assessments cannot do.

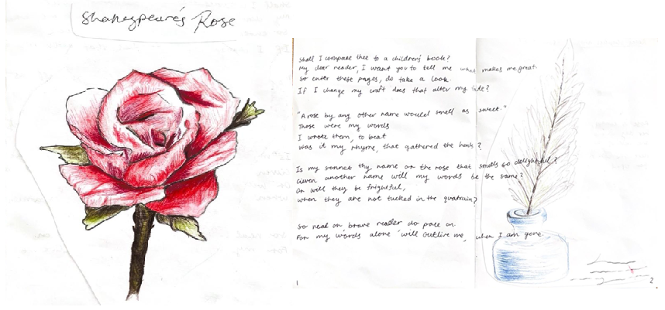

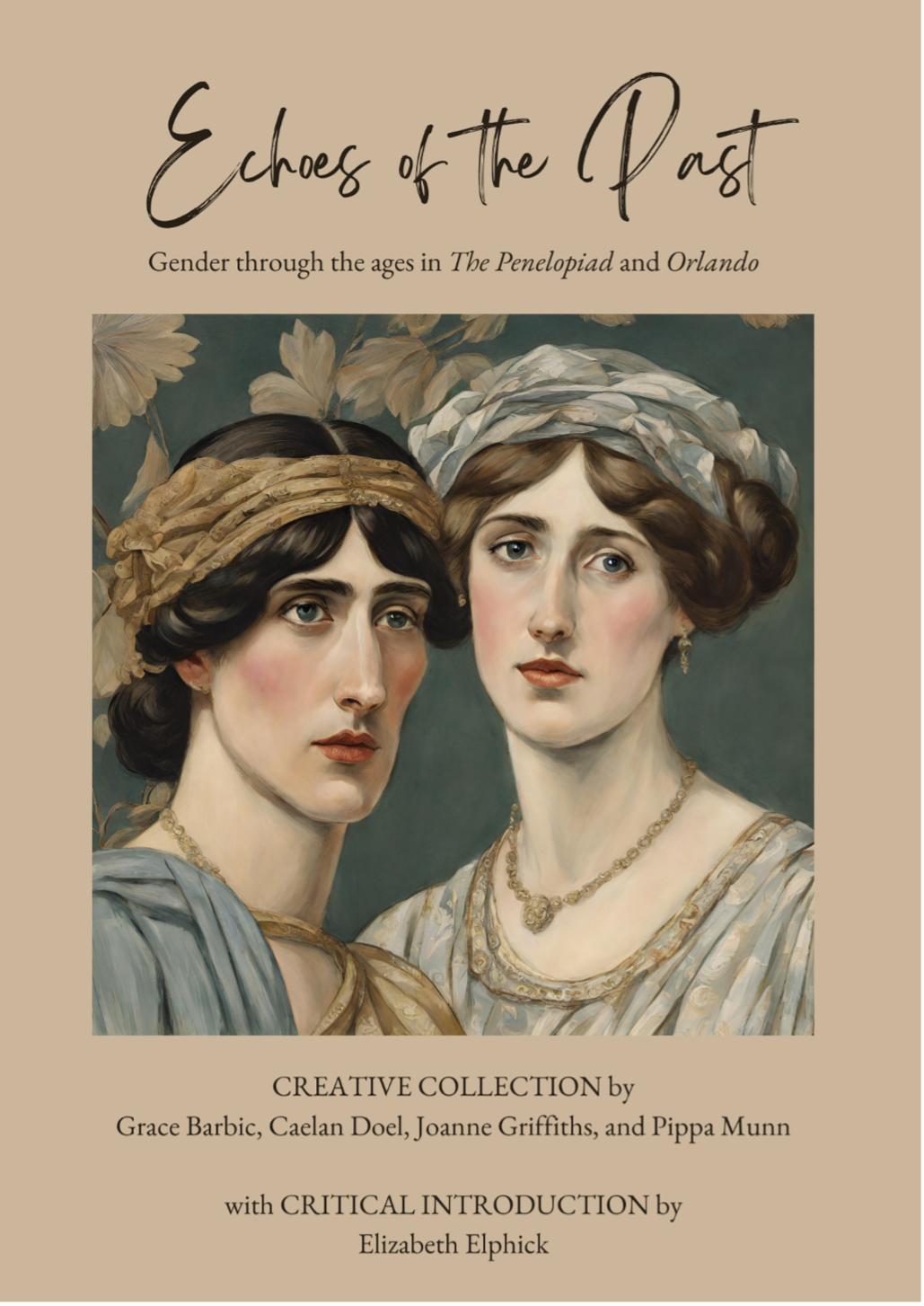

The combination of individual and team assessment produced some spectacular results. For example, Ava Corey created a watercolour on canvas for her individual assessment, with panels that responded to the written work of each of her fellow teammates (Figure 1). One team decided to look at genre and compared John Marsden and Shaun Tan’s picture book, The Rabbits, with Shakespeare’s Sonnets. This involved rewriting the picture book as a sonnet, and a sonnet as a picture book (Figure 2). Another team created a collection of creative works, featuring a critical introduction – this concept nicely balanced individual and teamwork skills (Figure 3). While, one other team chose to put together a pre-recorded short film that engaged with Taylor Swift’s Midnights album.

Figure 1. Individual contribution, titled ‘Spirit of the age’, 42x120cm, watercolour on canvas. Developed in collaboration with teammates’ written work. This project focused on Viginia Woolf’s Orlando and Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Figure 2. Individual contribution: Shakespeare sonnet rewritten as a children’s picture book to interrogate the role of genre. This team compared Shakespeare’s Sonnets with John Marsden and Shaun Tan’s award-winning picture book, The Rabbits.

Challenges and future iterations

The main challenges of this authentic assessment design related to teamwork, time and event management.

Students are often hesitant to engage in teamwork. I attempted to pre-empt these fears by clarifying the purpose of the assessment design and reinforcing its relevance beyond university. I provided resources on teamwork and required all teams to create a team contract (non-assessable) that required them to think about how the team would work together. Perhaps most importantly, I allocated weekly tutorial time for team meetings which included weekly check-ins with the convener. This ensured teams did not feel isolated and enabled speedy troubleshooting. Students were also required to complete self-reflections and peer evaluations twice across the semester to ensure accountability. Finally, the Festival assessment was divided equally into groupwork and individual work, so students did not feel anxious about teamwork negatively impacting their grade.

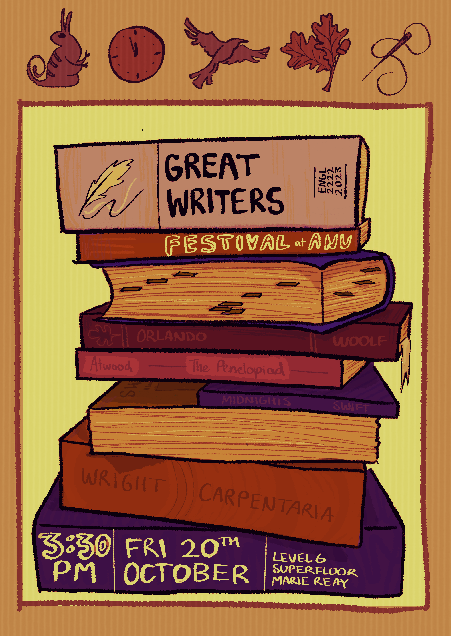

Due to the range of individual and team assessment, this course had a higher marking workload which is a challenge to be considered for future iterations. Further, unlike more traditional assessments, the event-focused design of the course required significant time from the convener and sessional staff for event management and administration. Thus, time management is a factor for conveners considering an assessment of this nature. Future iterations could incorporate student roles more explicitly in the event management, perhaps weighting this as part of their contribution. This semester, some students informally took on roles around promotion, with one student (Indi Jones) producing the Festival poster (Figure 4).

Figure 3 (left). Team project: Echoes of the Past collected creative works with critical introduction examining Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando.

Figure 4. Student-designed poster for the Great Writers Festival. Poster by Indi Jones. The poster includes icons that symbolise the key texts studied in the course.

Overall, this assessment design is immensely scalable and could be scaled up or down depending on available resources. As a trial, I weighted the Festival at 50% of the course grade. Future iterations could increase this percentage (ensuring it was distributed across iterative assessments), reducing other assessment tasks to alleviate marking load and to give students more time for their projects. Other similar models could also be trialled: in lieu of a festival, courses could run a conference or produce a collaborative publication output or even website.

While official student evaluations are yet to be received, anecdotally this course design has received strong support from the student cohort. Via email, one student wrote: ‘this course will be something I look back on very fondly for my time at uni’.

Dr Claire Hansen, Lecturer in English, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences

References

Biggs, John. “Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment.” Higher Education, vol. 32, no. 3, 1996, pp. 347–64, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871.

Biggs, John B. and Catherine Tang. Teaching for Quality Learning at University What the Student Does. 3rd ed., McGraw-Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, 2007.

McArthur, Jan. “Rethinking Authentic Assessment: Work, Well-Being, and Society.” Higher Education, vol. 85, no. 1, 2023, pp. 85–101, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y.

Villarroel, Verónica, et al. “Authentic Assessment: Creating a Blueprint for Course Design.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 43, no. 5, 2018, pp. 840–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396.

Wiewiora, Anna, and Anetta Kowalkiewicz. “The Role of Authentic Assessment in Developing Authentic Leadership Identity and Competencies.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 3, 2019, pp. 415–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1516730.