Playful approaches to teaching

One day my primary-school age son said to me, praising his classroom teacher, “she turns hard work into fun and games”. I laughed and said, “that’s funny, I do the opposite, I turn fun and games into hard work”. Having worked as a professional video game developer for many years and as a lecturer and researcher in video games, the irony was not lost on me. But for most of my career, the idea of marrying my teaching approach with my research and practice in game design had not occurred to me.

During my PhD, I developed a model of enjoyment in games, called GameFlow (2005). It was something that was missing from the literature at the time and I developed it out of need. My PhD was actually focusing on complex systems and artificial intelligence (AI) in games, but I needed a way to evaluate how my systems impacted player experience. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how smart your game AI is, if it doesn’t have an impact on the player.

The funny thing is that the GameFlow model was the most impactful thing that I did during my PhD, and it has become one of the most widely cited papers in game design. Apparently, others had the same need as I did. In 2020, I published a review of how my model had been used over the preceding 15 years (GameFlow 2020), in preparation for developing a new version of the model, GameFlow Affordances (2024). I found that most applications were for educational purposes, even more than for entertainment, and not just educational games – educational experiences more broadly. This hit home for me – other people were using my work to create, design and improve educational experiences, but I was not.

In 2022, I had the opportunity to go through the Educational Fellowship Scheme (EFS), in which the first exercise was developing my teaching philosophy. I found the best thing about the EFS was that it gave me the opportunity (or the nudge) to give myself the time and space to take a step back and think about my approach to teaching. I thought about who I was and who I wanted to be as a teacher, and I crafted my personal philosophy:

“My identity and integrity as an educator are strongly tied to games, play, and learning. Games facilitate the innate human need to learn, play, experiment, and put learned skills to the test. My research is closely intertwined with understanding what motivates humans to play, learn, and be challenged. I want learning experiences to be engaging, playful, and deeply rewarding. The key motivators are agency, mastery, and connectedness. Learners need to have choice and control, feel that they can meet the challenges, and learn in a social context. I aim to embed choice, flexibility, and opportunities for students to work at their own level, and to learn as part of a community. I aim to express these values in all assessment and practical and workshop activities.”

Penny Kyburz

The following year, I had the opportunity to develop a new course on Game Development. What better opportunity to put my new philosophy into practice? While I was teaching students to create playful experiences, I would use the same tools and techniques to craft their learning experiences.

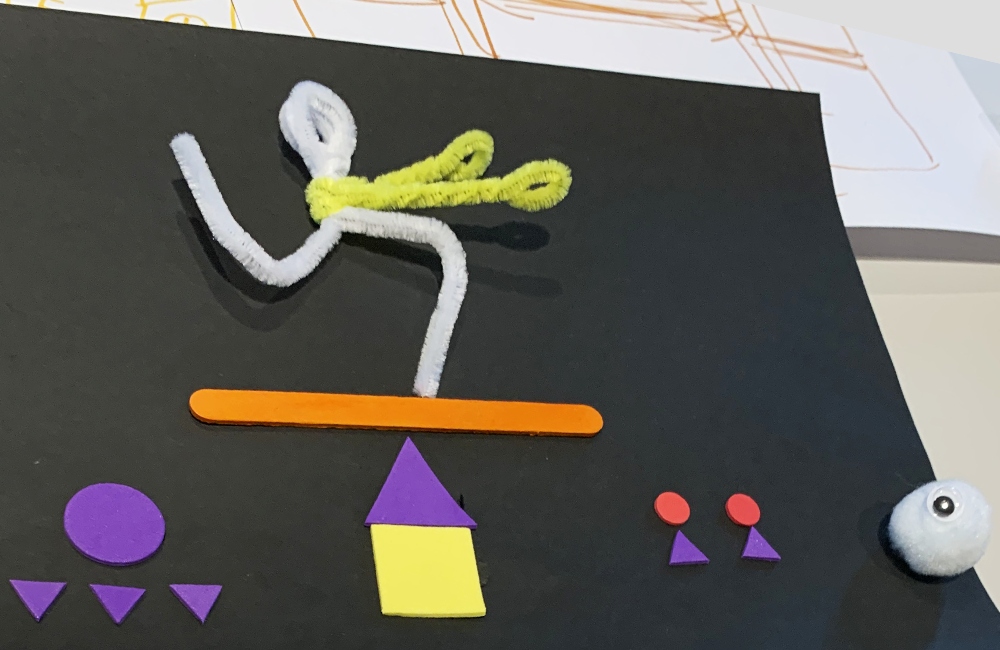

Student work created in the Game Development course

I teach my students that game design starts with thinking about the player experience. This might seem obvious, but it is more natural (and easier) to both focus on the content and mechanics (the what and the how) and to think about yourself as the player. The player experience is not about what the player will do or even how they will do it, but it is about how they will feel while playing. These lessons are directly translatable to teaching. My ‘learning experience’ is embedded in my teaching philosophy – “I want learning experiences to be engaging, playful, and deeply rewarding”.

I was ambitious in my approach to designing the Game Development course. I wanted to take my game design lessons and reward my students (with marks) for doing the things that mattered (learning how to make fun games) in a social context (workshops and team projects) with playful activities (such playing with crafts) and a deeply rewarding end product (publishing their own games). Along the way, they would learn game design theory and technical skills in game development, as well as production management and teamwork. They were deeply motivated by producing a publicly available game that they could get their friends and family to play – something to make them proud. I found that the students poured their time and effort into their games. They weren’t producing pieces of assessment that no one would ever see and that they would never think about again. They were creating something new and exciting, and the results were fantastic (see video below). I rewarded the students who created the top 5 games (as a surprise) with a certificate.

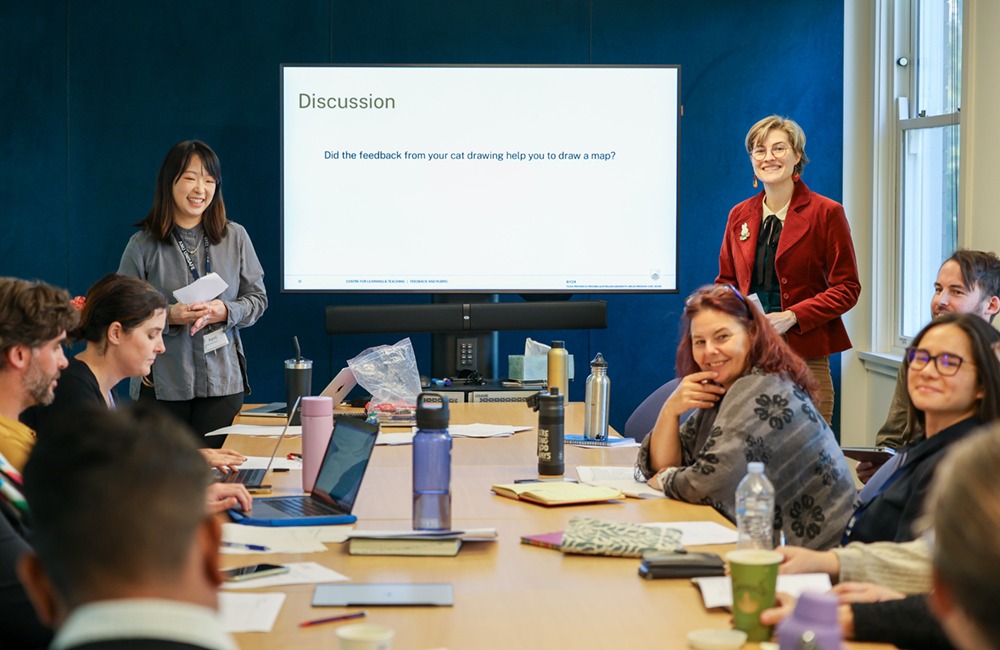

My primary learning activities were weekly workshops held in the Marie Reay superfloor. I split the class into half (180 students total) and ran two 2-hour workshops each week (80-100 students in each). I personally ran the workshops, with the assistance of 2-3 tutors in each class, as I wanted to have that personal facetime with the students. I told them what I expected them to achieve each week before class, but also provided them with everything they needed (to know, use, do) within the class. We held brainstorming sessions, physical prototyping with arts and crafts, shared ideas, and played and enjoyed each other’s games. My teaching materials were playdough, butcher’s paper, coloured pens, googly eyes, and bits and pieces. Students were required to collect evidence of their work each class to use in their ‘developer diaries’ and ‘prototyping reflections’. The workshops were always full. I had planned to cut lectures all-together, but I ended up running them for 8 weeks. In contrast to the workshops, lecture attendance dwindled to nothing. I will only run an orientation lecture this year.

My own research has shown that at the core of player experience – the reason why games are enjoyable – is learning. Learning and play are inextricably entwined: humans innately learn through play, and enjoyment is our evolutionary reward for learning. I have always taught my students to make games enjoyable by focusing on the opportunities for learning. Now, I am finding my way to making learning enjoyable by finding the opportunities for play.

Professor Penny Kyburz, Associate Director (Engagement & Impact), School of Computing, College of Engineering, Computing and Cybernetics (CECC)